The Virgin Suicides takes place in a bare Detroit suburb in the 70's and Twin Peaks in a secluded Washington industrial town at the time it was made in the 90's. Neither towns distract from their sadness with pastels and picket fences, as they slowly give up on holding up an illusion of a friendly town. They are yellow and gray and chipping paint and bags under their eyes. It's the perfect place for the kind of tragedy no one can figure out how to justify. Laura Palmer was murdered at 17, and the Lisbon sisters, 13-17, all killed themselves.

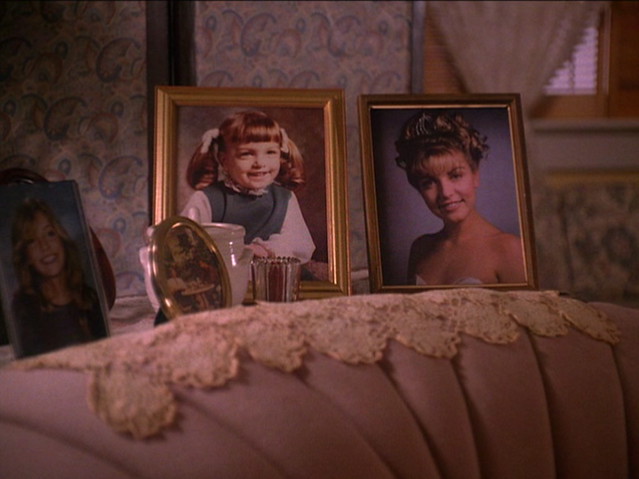

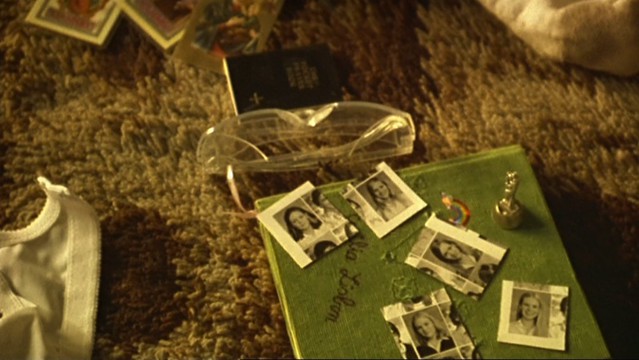

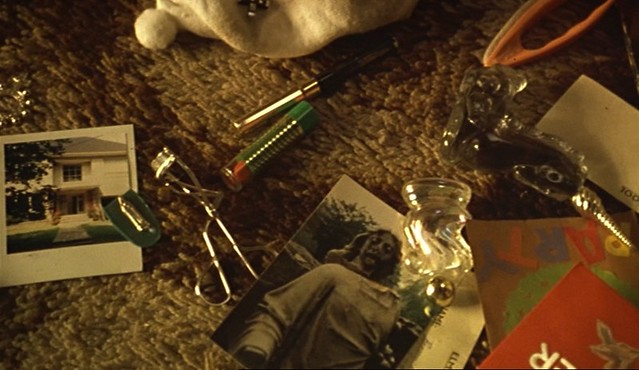

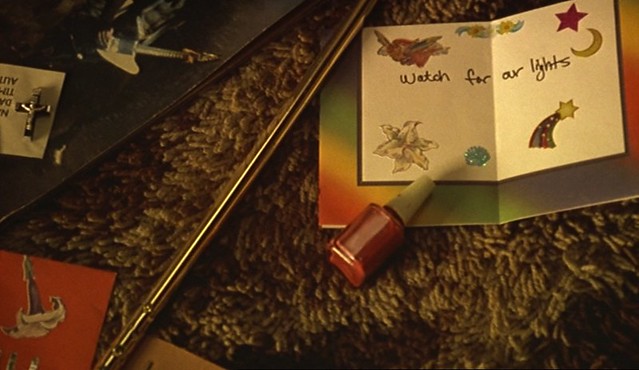

The show and movie are both known for giving extra camera time to the details of the ways their characters live, keeping specifically with the middle-of-nowhere feeling. But the moments spent on details of material memories of the girls align with this feeling most perfectly, combining the mixed pain and comfort of remembering someone who is now gone with the mixed pain and comfort of living in a place so secluded. The point that both Twin Peaks and The Virgin Suicides make to focus in on seemingly minor details -- a photo on a mantle, an eyelash curler -- when the larger story is so tragic gives pathetic tchotchkes and tiny memories significance. Depressing details of boring houses in boring towns become weirdly beautiful when they end up the only remnants of people who are now dead, leaving the neighborhood boys to smell the Lisbons' stolen lipstick with wistful desire and Mr. Palmer to dance in the living room with Laura's photo to keep from crying.

These are the only memories we get of these girls, too. Laura is found dead in the first episode, occasionally recalled throughout the series with flashbacks and dreams, primarily remembered with the homecoming photo that always ends the show. But a video tape of her dancing at a picnic with a friend that's shown in the pilot is when we first fall in love with her spirit, and first notice that something is at work underneath her joy as a muffled voice begs "help me" over a close-up on her eyes.

Though the Lisbon sisters actually are alive for the majority of the movie, we hardly know them any better than the boys across the street do, and join them in their search for any clues or contact. Half of the idea of the Lisbons is definitely a teenage boy fantasy about blonde unicorn fairies, but the moments we get to witness of them all spending time together -- lying strategically like Tetris pieces on the same bed, fixing their hair for the spring dance, smoking together in the school bathroom -- indicate a kind of unspoken bond they've created amongst themselves out of colors and songs and stares. Along with being the total babes the neighborhood boys fawn over, they're complicated and human, mysterious and intriguing, already thinking about things you're not supposed to consider until you've exhausted the world of your bedroom and school and want more answers. As it goes, not all answers are as dreamy as the world the Lisbons had previously pieced together. One scene focuses in on Lux Lisbon in a class photo while one of the boys recalls the tips the school administration had told them to look for in their possibly troubled peers: "Were the Lisbon girls' pupils dilated? Had they lost interest in special activities, in sports and hobbies? Had they withdrawn from their peers?"

It's strange to feel strongly about characters who are talked about more than they're shown, but Laura and the sisters have turned into faces for me that feel less like fictional characters celebrated in the outside world and more like local legends, personal legends, combinations of various teenage figures I watched avidly when I was little, of my sisters' friends and dad's students and cool and weird and pretty babysitters, who I so desperately wanted to be friends with, if not be.

The "little things in life" aren't supposed to be this morbid, but right now I'm more affected by ugly living room decorations than by flowers. I'll take a few extra moments to look at a tacky ceramic on a thrift shop shelf or someone else's school photo hanging in their stairway or a friend's older sibling's souvenir of adolescence left on the dresser of her old room. All of a sudden there can be something really endearing and personal about a pitiful trinket, and I've become more nostalgic for all those small bedside table objects my sisters and their friends once held to such importance. As another person who fell in love with Laura Palmer and the Lisbon sisters, I feel compelled to nurture my own memories of the girls, paying close attention to any cheesy iconography or vomit pink figurines or crackly ashtrays or shiny stickers I may come across. Even if it is more about a romanticized idea of this age that ended up less true than a younger me had hoped. Even if it is less for the sake of paying respect to fictional characters and more for my own fantasies.

211 comments:

«Oldest ‹Older 201 – 211 of 211Identifying Your Style

First, determine the style that best fits your story. Whether it's whimsical, realistic, or abstract, finding the right match is crucial.

https://www.blueberryillustrations.com/

Loved the style insights! For vibrant photos, consider a Colour correction service to enhance your visuals!

The show and movie are both known for giving extra camera time to the details of the ways their characters live, keeping specifically with the middle-of-nowhere feeling. But the moments spent on details of material memories of the girls align with this feeling most perfectly, combining the mixed pain and comfort of remembering someone who is now gone with the mixed pain and comfort of living in a place so secluded.

cricut vinyl printer

cricut joy vinyl bundle

cricut coffee mug press

heat press machine cricut

best cricut for stickers

cricut explore one

cricut heat mat

Find Cheap & Non-Stop American Airlines Flights NYC to Delhi in 2025 And also Buy Now ECO AROGYAM MULTIFLORA HONEY (NEW) – Pure, Natural, & Eco-Friendly Health Booster | Asclepius Wellness Products | AWPL product | Herbal, Healthy & Organic and alsoAuthentic Desi Ghee Homemade Thekua – Traditional Bihari Sweet Cookies No Maida |Traditional Bihari Thekua| Indian Sweet Thekua |

Looking for job opportunities? Check out Classified ads Kolkata for the latest openings in various industries. Stay updated with fresh listings and land your dream job easily!

This is a well-written and insightful article that effectively covers its topic with clarity and depth. The author presents complex ideas in an accessible way, making it easy for readers to understand even the more intricate details. Suction Machine Rentals in Ahmedabad | Wheelchair Rentals in Ahmedabad

Your article is greatfull and thanks for sharing this article in my family. RPSC 2nd Grade Teacher Syllabus 2025 your article is very happy more aticle is share.Bihar CET BEd Apply Online 2025 : Check Application Dates, Exam Pattern & More Rajasthan Jail Prahari Answer Key 2025: राजस्थान जेल प्रहरी संभावित आंसर की जारी

Thank You So Much for sharing.I have found it extremely helpful.

Sattva Forest Ridge

Such a thoughtful post! Anyone looking for the Best kids school Rajouri Garden should read this. The way you described the importance of early learning, social skills, and caring teachers makes this blog both informative and inspiring for parents.

I found this article very engaging and informative. Promo Codes uae are becoming increasingly important for online shoppers who want dependable discounts. I’ve personally noticed that using verified coupon codes reduces checkout issues and ensures actual savings. Thank you for explaining this topic so clearly and helping shoppers make smarter purchasing decisions.

More info:-

Verified Coupons,

Cashback Offers 2026

Discounts

Post a Comment